Judicial Corruption

Was Ice Cream Magnate Tom Carvel Murdered?

Carvel's niece Pamela Carvel thinks so. Others say Pamela is making this alleged murder up to pursue her greedy agenda to get the family fortune. No matter what, this story is a great read.

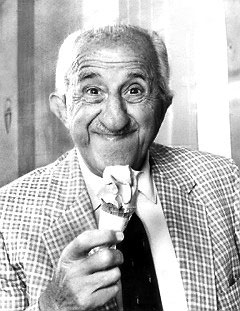

Tom Carvel

by Joel Siegel, Portfolio, August 2008 Issue

LINK

Tom Carvel's ice cream empire churned up a substantial estate and a bitter, Dickensian fight

over his money. Now a lawsuit asks, was he murdered?

In what would be the final weekend of his life, Tom Carvel drove to his country home in upstate New

York, deeply depressed. He'd built a namesake national chain of 850 ice cream shops, developing

some of the fast-food and franchising concepts that changed how America eats. His sandpaper-voiced

pitches in commercials—“Thinny-Thin for your fatty-fat friends,” he said in one spot—had made Carvel a

household name. He golfed with Bob Hope and did a guest turn on Late Night With David Letterman . He

had recently sold his chain for $80 million, but he held on to a 100-room motel, 40 properties leased to

Carvel franchisees, and a golf course in Dutchess County, New York. At 84, Carvel still was going to work

every day.

But there were deepening problems inside his empire. Carvel confided to an associate that he no longer

trusted Mildred Arcadipane, his corporate secretary of 38 years, or Robert Davis, his longtime lawyer and

close financial adviser. Carvel had come to believe that they were scheming behind his back, maybe

stealing from him. After agonizing for months, he arrived at his country home on Saturday determined to

march into his office on Monday and fire his lawyer and relieve his secretary—a mercurial woman,

according to many who knew her—of her considerable power.

But Carvel never got the chance. He was found dead in his bed that Sunday morning in 1990, the victim, it

appeared, of a heart attack. Instead of being dismissed and demoted, Davis and Arcadipane returned to

work and began to take command of Carvel's business and personal finances. The Carvel estate, officially

valued at $67 million, spurred what one lawyer calls a “feeding frenzy”; nearly 18 years later, a bitter fight

rages on. In most estate battles, family members square off against one another. But the principal fault lines in this case have put Davis, Arcadipane, and the multimillion-dollar charity that Carvel left behind on one side, and Carvel's widow, Agnes, and his niece Pamela Carvel on the other. The Carvels had no children, and Agnes “was frozen out of everything,” Pamela contends. “She was denied millions that Tom wanted her to receive.”

In 2007, after years of digging by private investigators in Pamela's employ, the case took a bizarre turn.

Pamela filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, alleging that Carvel's death resulted

in “fraudsters…controlling all Carvel funds to the exclusion of the Carvels.” She asked that her uncle's body

be exhumed for an autopsy to determine if he was murdered as part of the alleged scheme. The petition

concludes with a question: “Will the truth finally be known?” And with that, one of the most contested estate fights in New York history also became a murder mystery.

Pamela says she has circumstantial evidence against several former Carvel employees, but a great deal of

her ire over the years has been aimed at Davis and Arcadipane, who not only continued to work for the

company but also battled Agnes for years over the Carvel fortune from their seats on the Thomas and

Agnes Carvel Foundation board—seats they gained through a document whose validity has been called into

question. Both eventually were forced to resign from the board for misappropriating foundation money. Their families and lawyers scoff at any notion that they would ever have harmed Tom Carvel, but even if they had, neither will face justice. They are dead.

By any measure, the Carvel case is a legal colossus. More than 40 lawyers have had a hand in it. Legal

fees and commissions have already drained more than $28 million from the Carvel fortune, according to

Leonard Ross, one of Agnes' former lawyers. Save for Carvel's widow, it is hard to find a guileless

participant. Pamela casts herself as the selfless protector of her uncle's millions and her aunt's interests. To her opponents, she's just a desperate relative out for a big financial score. In one of the many lawsuits

involving estate funds, a state judge in Florida ruled that there was “strong evidence of fraud” in the way she once tried to collect more than $10 million from the estate. Still, Fred Welsh, a former New Jersey police detective hired by Pamela, tells me that he has uncovered enough circumstantial evidence—including the possibility that Carvel's death certificate was forged—to warrant a homicide investigation.

The battle has played out in three U.S. district courts; state courts in New York, Delaware, and Florida; and

in London. It enjoys a certain notoriety in the suburbs north of New York City, where Tom and Agnes Carvel

lived in the gentle hills of Ardsley. Four trials have been held in Westchester County, New York; a fifth is

ongoing. Four of Carvel's executors have died. When I phoned the Westchester County Courthouse to ask

about examining case files, a clerk told me, “I am making the sign of the cross now.” I spent most of a day plowing through five large boxes bursting with pleadings and rulings before a court official said

apologetically, “We've found more.”

Pamela claims that her uncle once told her that he was worth $250 million, which would mean that tens of

millions of dollars in assets have vanished. One thing is certain: Events have not turned out as Carvel

wished. His plan to provide for his widow and funnel millions to small charities in the towns that supported

Carvel stores backfired, in part because of the unwieldy, complex nature of the estate that he himself

approved after consultation with Davis, his lawyer. “He was always fearful that somebody was after his

money,” says Ginny King, a longtime friend.

And in the end, he was right.

Born in Greece in 1906, Tom Carvel immigrated to New York with his parents and six siblings in 1910. As a

young man, he test-drove Studebakers, played drums in the Borscht Belt, and fixed cars. After being

diagnosed incorrectly with tuberculosis, he set out for the fresh air of Westchester, and with $15 borrowed

from his future wife, he began selling ice cream from a beat-up vending truck. One hot weekend in 1934, he suffered a flat in the village of Hartsdale. Flagging down motorists to buy his melting ice cream, Carvel realized he could do more business from a fixed location. So he remained for the summer, eventually saving enough to make a down payment on a nearby building. It became the first Carvel shop.

With some tinkering, Carvel discovered how to instantly freeze ingredients to produce a creamy ribbon of ice cream at the flick of a switch. It was the first soft-ice-cream machine of its kind. One store grew to many, and by 1950, 21 stores were operating under the Carvel name. With that, Carvel joined a group of

franchising pioneers, including A&W, White Castle, and Howard Johnson's, that were creating roadside

chains that served up what would become known as fast food. Still, the ice cream business was a warmweather enterprise, and Carvel needed to generate store traffic throughout the year. Again, the ice cream gods intervened. Pieces of crumbled cookies accidentally fell into a vat of soft ice cream placed in a freezer, and when the hardened batch was discovered, it led to another innovation: the Carvel ice cream cake.

Carvel's climb might have been even more astounding had he not rejected an invitation from a milkshake machine salesman named Ray Kroc to join him in a fledgling California hamburger business named

McDonald's. “Tom claimed it was his biggest error,” says Thomas Kornacki, a Carvel vice president in the

1990s who worked for the company for 23 years.

Tom Carvel had a special knack for promotion—and self-promotion. He sponsored Little Miss Half-Pint

contests for young girls and made franchisees attend an 18-day course he called the Carvel College of Ice

Cream Knowledge. His raspy, ad-libbed appearances in the company's commercials were ridiculed, but they

were memorable and sales soared. The idea of the C.E.O. as pitchman would catch on and influence other

company heads, like Frank Perdue and Lee Iacocca. In his ads, Carvel seemed benign, but in real life, he

was no Mister Softee. He battled franchisees all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, winning the

groundbreaking right to require them to buy all ingredients and supplies from him, even the napkins.

Despite his wealth, Carvel lived simply. He wore polyester suits and hectored subordinates who didn't drive

modest American cars like he did. Visitors to the Carvels' Ardsley home were amazed to find couches

protected by plastic slipcovers. His office was an oversize motel room with furnishings that would have gone

begging at a lawn sale. Yet T.C., as friends called him, could be generous; each Christmas, he gave gifts of $10,000 (tax free) to dozens of nieces and nephews.

By the late 1980s, however, Carvel's fortune had become a burden. By then, he was in his eighties. Without children, he wondered what would happen to all he had accumulated. After wavering for months, he reluctantly sold his ice cream operations in 1989 to Investcorp, a Bahrain-based company that owned

Tiffany & Co. and Gucci. “He didn't trust anybody in his family or in his executive group to grow the brand,”

Kornacki says. “The company was his legacy, and he didn't want it to die.”

Carvel put his personal affairs in order too. One cold Saturday night in February 1988, Tom and Agnes

excused themselves from a dinner party to sign identical wills naming the Thomas and Agnes Carvel

Foundation as the beneficiary of their fortune after their deaths. Carvel was quite clear about how he

intended to bestow his estate. If he died first, Agnes was to receive all the income his estate generated, plus quarterly payouts from a trust fund. The Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation was to receive all that was left—once Agnes died.

Overseeing this estate would be seven executors, Arcadipane and Davis among them. That number is

unusual, but Carvel was convinced that the seven would serve to check and balance one another,

safeguarding his money. One of the people who helped fashion the plan was Davis, his lawyer. Whether

Carvel was steered into this plan by unscrupulous advisers or driven to it by his own fears about the fate of

his fortune is an open question. But he had not been dead for more than a few months before one thing

became clear: The elaborate plan, rather than creating checks and balances, set up factions that came to

feud over and feast on Carvel's fortune. It was turning into an estate disaster of monumental proportions.

The wild card in Tom Carvel's life seems to have been Mildred Arcadipane. A slight woman, she began

working for Carvel in the early 1950s, fresh out of secretarial school. Her job was her life; in the 38 years

that she was employed by the Carvel corporation, co-workers recall her taking off just two days—to attend

her father's funeral. She never married, choosing instead to care for her elderly mother at home. By the

1980s, evidence in the many court cases shows, she had become a force inside the company. The

accounting and payroll departments had begun to report to her. She “knew the nuts and bolts of the

company,” and with her “hot temper” and “iron fist,” she knew how to get things done, Kornacki recalls. She could also be despotic. Some employees complained that underlings who crossed Arcadipane might find themselves without a job or that their health insurance had lapsed.

She had her way with Tom Carvel too. Arcadipane often cursed and shouted at the boss and locked him out of his own office dozens of times, a longtime driver for Carvel testified. On three occasions, Carvel sent him to New York City to buy jewelry as a peace offering. “When she lost her temper,” the driver said in the deposition, “it would require almost a straitjacket.” Asked why he kept Arcadipane on, Carvel once said cryptically that she had him “over a barrel,” according to another affidavit. Employees whispered that Carvel and Arcadipane, far from being just close business associates, might once have had an affair.

Pamela Carvel was close to Tom too. She grew up in Queens, New York, the eldest daughter of Tom's

brother Bruce. Tom and Agnes treated her like the child they never had. As a teenager, she spent her

summers living with them and serving ice cream at their Hartsdale shop. Tom took care of her college tuition bills and hired her to make inspections of Carvel stores. When her uncle died, Pamela, who was working and studying abroad, “got a call to come home,” she says. “My aunt told me she needed help.”

Tom had made Pamela one of the seven executors of his estate. She returned to New York in December

1990, she says, to find an avalanche of suspicious transactions involving the Carvels' finances. Bank

accounts were being closed and opened, apparently without Agnes' knowledge, and large sums of money

were being transferred between Carvel accounts, her lawyers told me. In the middle of these matters,

Pamela says, were Davis and Arcadipane. Davis wasn't a Carvel lifer, but he had a long history with Tom

Carvel. While working for a Manhattan law firm, Davis had taken Carvel on as a client in 1969 to advise him on how to take his company public that year. Davis later helped negotiate the 1989 sale to Investcorp.

Hints of trouble surfaced before Carvel was even buried. As Agnes attended her husband's wake, Davis

entered the Carvel home without her permission to search for Tom's will, bringing a locksmith to crack open the couple's safe, court documents show. Shortly thereafter, Arcadipane began shredding records at the office, defying orders from other Carvel executors that she stop. The shredder was silenced only after

Pamela burst in and cut the electric cord herself. Through it all, Carvel's will could not be found. It had been given to Arcadipane for safekeeping, but she claimed it was lost. Its disappearance delayed Carvel's

executors from officially assuming control of his estate, leaving Davis and Arcadipane in command for

months.

Agnes, during this period, seemed overwhelmed. Davis was pressuring her to loan the business $500,000,

saying there were cash-flow problems. Agnes demurred, on the advice of Pamela, who considered the

request improper. But Davis persisted. He sent another of Tom's employees to Florida to talk to Agnes

while Pamela was in New York, and this envoy convinced the widow to supply the funds. Meanwhile,

Thomas Reddy, a lawyer and a family friend, got Agnes to sign papers creating a trust account for her

money. Three trustees would manage the funds and have the authority to make distributions to her. Known as the Florida trust, it was touted as a safeguard for Agnes' assets—but for the widow, it would become a nightmare.

Unusual things were also happening at the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation. Davis emerged as the

foundation's first paid president, at a salary of more than $100,000 a year, and board members—including

Arcadipane—began drawing stipends, records show. The payments were troubling to Agnes because she

and Tom believed that any work for the charity should be done for free. Agnes also became bewildered by

the foundation's abrupt shift in direction. Although it bore their names, it was focused more on making six and seven-figure grants to big, established institutions than on making small grants to the grassroots groups Tom and Agnes favored. Worse for Agnes, a serious flaw emerged in the estate plan. With the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation now under the sway of Davis and Arcadipane, it took an aggressively adversarial position, questioning Agnes' spending and even challenging her right to continue Tom's practice of giving gifts of $10,000 at Christmas, according to Agnes' lawyers. (The foundation denies this allegation.) The charity had a reason to be aggressive: Every dollar that Agnes spent or gave away of her husband's fortune would mean less money to the foundation when she died. Agnes and Pamela were rapidly coming to the conclusion that the two people Tom suspected of cheating him before his death had become their enemies too.

As Pamela and Agnes plotted to regain control of the foundation, they got some help. The New York State

attorney general's office opened an investigation in 1991. Its findings were shocking: The inquiry discovered that the charity paid $55,000 in tuition for Arcadipane's nephew and two others and tried to camouflage the spending as grants. The attorney general also questioned Davis' and Arcadipane's roles in the foundation's sale of Carvel stock, which reaped a quick $5 million profit for some company employees, including $300,000 for Arcadipane.

In August 1993, the attorney general filed a civil lawsuit seeking the ouster of Davis and Arcadipane from

the foundation and the repayment of nearly $1 million, plus money paid to cover their legal fees. Far from

being chastened, Davis helped prepare a memo to foundation members warning that his and Arcadipane's

removal would provide the family “with an opportunity to assume control of the foundation.” The memo

found its way to the Carvels. To Pamela and Agnes, it was a smoking gun. “The foundation took an attitude that the Carvel family should not have any say in the operation of the Carvel Foundation,” Agnes' former lawyer Ross says. “Davis was behind that.”

Agnes fired off a letter to the foundation. “I am appalled that Mr. Davis views this foundation as his own

private charity, where the Carvel family is to be treated as the enemy,” she wrote. Pamela sent a scalding

note to Arcadipane: “Obviously, you feel no responsibility nor the slightest twinge of gratitude” to the man

and the company that had “made a secretary into a millionaire!” The battle was on. Agnes and Pamela went to court to oust Davis and Arcadipane as foundation directors and executors of Tom's estate. The foundation countersued, accusing Agnes and Pamela of meddling in its affairs.

The fighting turned so nasty that Davis and Arcadipane asked Judge Albert Emanuelli of the Westchester

County Surrogate's Court, in White Plains, New York, to investigate Agnes' mental competency. To Agnes'

lawyers, it was an effort to silence the widow for good. Davis and Arcadipane said they just wanted to make

sure that Pamela was not controlling Agnes. In an affidavit, Arcadipane said she looked on Tom and Agnes

“in many ways as parents” and believed that “they reciprocated the depth of feeling.” She continued, “Sadly, since Mr. Carvel's death, his niece Pamela has sought to alter Mrs. Carvel's feelings toward me and view of me and to rewrite history.... She has undertaken to level accusations at me...that are scandalous and shameful.”

Pamela Carvel is 59 and single. She cuts a bohemian figure, tying her bottle-blond hair into a braid that falls to her waist. The estate fight is a full-time occupation for her. By her own accounting, she has plowed

through millions of dollars and fallen into debt to help her Aunt Agnes and stop what she calls the

plundering of Tom's estate. Pamela can be strident and difficult; she has had at least four law firms

represent her. She now accuses some of those lawyers of betrayal. Still, a few of them speak of her with a

weary admiration. “Pamela Carvel is a very tough lady who was fiercely dedicated to her aunt and to the

memory of her uncle,” says John Lang, one of Agnes' former lawyers. “My sense is that she was completely sincere in what she was doing.”

Pamela's critics ardently disagree. Betty Godley, Agnes' niece, filed an affidavit in Surrogate's Court

accusing Pamela of manipulating Agnes for “her own insatiable greed.” Godley tells me, “I think there were

great expectations on Pamela's part of money coming her way.” Never close, Pamela and Godley have not

talked in more than 10 years. Their split demarcates a family fracture in the Carvel case. “From day one,

there was a paranoia to Pamela that was incredible,” Godley says. “Everybody and anybody was an

enemy.” Since 1991, Godley has received more than $400,000 in commissions as an executor of Tom's estate and one of the three people overseeing Agnes' Florida trust. Still, she talks of her participation as a burden that she wishes would end. “I have five kids, a family, everything she doesn't have,” Godley says of Pamela. “This has been Pamela's life for 17 years.”

The seeds of Pamela and Godley's split were planted six months after Tom's death, with the creation of the Florida trust that was supposed to be a vehicle to safeguard Agnes' money. Godley was the only family

member among the trustees. Pamela has always seen Godley's appointment as a ruse. “That was the only

way to make it look legitimate, by having a family member on it,” she says. But after the trust was created, Agnes “no longer had any money in her own name,” she adds.

Indeed, in the spring of 1994, things turned bleak for Agnes when, at roughly the same time, the two trusts that doled out her funds—the Florida trust and the trust set up by Tom, which contained $26 million and was overseen by Davis, Arcadipane, and two other trustees—both stopped making payments to her, according to a lawyer for Agnes. Both trusts used the same rationale—that others were manipulating Agnes, who therefore couldn't be trusted with her own money. Ross, her former lawyer, saw a more sinister motive: “Mrs. Carvel was being squeezed, I think, to stop all the litigation.”

Agnes and Pamela were furious at Godley for withholding the money. The breach became permanent in

1995, when Pamela arranged to have $2 million moved from a Carvel corporation account whose ownership

was in dispute into a Swiss bank account registered in Agnes' name. Pamela said the money had been

owed to Agnes and that she had dutifully notified the required parties. But Godley went to court to challenge the transfer, and Judge Emanuelli of the Surrogate's Court ordered that the money be placed in escrow.

Godley and her aunt would never talk again.

By the middle of 1995, the Carvel widow, now 86, was in turmoil, bewildered by the endless swirl of

litigation. She was upset at her financial predicament and fearful that Judge Emanuelli, whom she had

come to view as hostile, would declare her incompetent, stripping her of whatever control she still had over

her life. So she sought refuge in London, moving there with Pamela to live out her days, she hoped, in

peace. Sally Boynton, a Westchester County lawyer appointed by the court to be Agnes' legal guardian, took Agnes and Pamela's side after flying to London to judge Agnes' competency for herself. The widow, Boynton would later tell the court, had become the victim of the “unscrupulous dealings of untrustworthy people” and had moved to London “to gain control over her assets to prevent ?the thieves from stealing from her.' ” Boynton also wrote that Agnes expressed “unequivocally” her trust in Pamela to handle her affairs.

Godley saw it quite differently. She charged that Pamela had become a Svengali, “hiding” Agnes in London

in an attempt to thwart an inquiry into Agnes' competency. “I feel a heinous crime has been done to my

aunt,” Godley wrote in an affidavit filed in the Surrogate's Court. Judge Emanuelli forced Boynton to resign

her guardianship, and he replaced her with Marc Oxman, a lawyer who at that time was the executive

director of the Westchester County Democratic Party.

Oxman was far more skeptical of Agnes' competency and Pamela's motives. In his report, Oxman wrote that Agnes had been “manipulated and controlled by those individuals who did not have her best interests atheart.” As the battle raged, Agnes died in London in August 1998, at the age of 89. Yet even in death, she could find no peace. Her body remained in cold storage for about a month while both sides fought over whether to allow an autopsy to determine if she had suffered from dementia. Pamela, who opposed the examination, prevailed and quickly cremated her aunt's remains.

Rather than hasten a resolution of the case, Agnes' death complicated matters, for now there were two

estates to fight over: Tom's and Agnes'. Arcadipane and Davis had resigned from the Carvel Foundation in 1996, in a deal with the New York attorney general's office to settle allegations of wrongdoing. Arcadipane died in 2002, at age 74, of a heart ailment. Davis died sometime later. But that didn't end the foundation's fight with Agnes' representatives.

Indeed, the charity has continued to be a fierce and formidable opponent of Agnes' attorneys and Pamela in their fight over Tom Carvel's millions. The foundation has approximately $36 million in assets, according to its most recent published tax records, from 2005.But today, the charity is connected to the Carvel family in name only. No family member sits on its board. Its directors have paid themselves more than $1.3 million in salaries since Tom Carvel's death, including about $43,000 annually to the foundation's president, William Griffin, the multimillionaire chairman of the Hudson Valley Bank, based in Yonkers, New York. Moreover, the charity has spent many millions battling for the Carvel fortune. In 1998, it was instrumental in torpedoing a proposed settlement that would have ended all litigation and given Agnes $8 million—a fraction of her husband's estate.

The foundation didn't respond to a request for comment on this; indeed, officials declined to be interviewed. The charity issued a statement that said, in part, that “Thomas and Agnes Carvel established the foundation and left the bulk of their estates to it to provide charitable grants to needy children, and the foundation is focusing its energies on fulfilling that mission...rather than responding yet again to Ms. Carvel's baseless allegations.”

And still the litigation continues. The latest chapter, playing itself out in the Surrogate's Court stems from a rare, albeit posthumous, victory for Agnes Carvel. In June 2003, five years after she died, a Surrogate's

Court judge ruled that she had been denied $7 million in income generated by Tom's estate during her

lifetime. The current trial is about what to do with this money and $3 million in other assets. The foundation is claiming all of it as the final beneficiary named in Tom's and Agnes' 1988 wills. (Tom's will surfaced several months after his death.) Agnes' lawyers argue that because she was wrongly denied the funds while she lived, her new London executor should decide how the money should be spent.

Pamela also made a play for the funds. After obtaining a $15 million judgment in a London court against her aunt's estate for money Pamela says she spent in caring for Agnes and providing for her legal

representation, she then tried in three separate American courts to collect the money from Agnes' U.S.

assets. But she did so without informing the Carvel Foundation—conduct that caused a Florida judge to

suggest that Pamela may have committed fraud. In June 2007, a judge in London removed Pamela as the

executor of Agnes' British estate and concluded, “Her every act has been calculated to promote her own

personal interests and prejudice those of the foundation.” Meanwhile, the case, which is expected to drag on at least through the end of this year, continues to devour the Carvel fortune.

And what of Pamela's most provocative theory, that the ice cream king, rather than succumbing to heart

disease, was murdered? Arcadipane's brother, Charles, now 78, says suggestions that his sister might have killed Carvel are ridiculous: “My sister could not hurt a fly.” Davis' last lawyer, Katharine Conroy, says the murder allegations “should be taken in the context they are made and weighed against the person who is making them.”

Boynton, Agnes' former guardian, says “nothing would surprise me in this case” given “the sense of

entitlement and greed some of these people had toward the Carvel money.”

Indeed, questions persist. Welsh, the former New Jersey detective Pamela hired to investigate the case,

says he uncovered circumstantial evidence that suggests someone might have fatally tampered with

Carvel's heart medicine. Old friends of the Carvels who were staying at the Carvel home the weekend Tom

Carvel died told Welsh of an odd development: They got a call from a Carvel employee within hours of

Tom's death telling them to remove all prescription drugs from his medicine cabinet. The request befuddled them, but they complied. Welsh also says he was suspicious of how quickly Carvel's body was whisked away to a New York City funeral home. In the Carvel case's vast paper trail, one item stands out. Pamela's investigators say they tape-recorded Tom's longtime physician, Robert Athans, saying that he does not remember signing Tom's death certificate even though it bears his signature. The doctor declined to comment for this story. If the death certificate was forged, who did it, and why? Was it to prevent an autopsy?

A federal judge in Fort Lauderdale ruled in May 2007 that Tom's exhumation is a matter for New York courts to decide. Pamela says she hopes to file an exhumation request in New York soon. And if the request is denied, or if an autopsy proves nothing, will that be the end of it? In one of my last conversations with Pamela, she talked of the exhumation request as if it were her final card to play, but later she recanted. “In Florida and in Delaware...I am still going to go after the bastards,”

she says, cataloging a list of possible lawsuits and legal actions. “I have nothing left now. So what do I have to lose?”